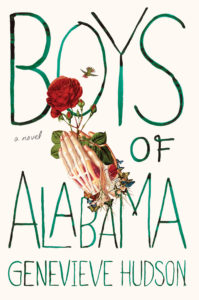

photo: Nick Curley

In this bewitching debut novel, a sensitive teen, newly arrived in Alabama, falls in love, questions his faith, and navigates a strange power. While his German parents don’t know what to make of a South pining for the past, shy Max thrives in the thick heat. Taken in by the football team, he learns how to catch a spiraling ball, how to point a gun, and how to hide his innermost secrets.

Author Michelle Tea calls Genevieve Hudson’s debut novel BOYS OF ALABAMA, “a gripping, uncanny, and queer exploration of being a boy in America, told with detail that dazzles and disturbs.” We had the pleasure of getting to “meet” Hudson when they did a recent Reader Meet Writer virtual event — and immediately wanted to chat with a bit more. Hudson graciously answered a few questions for us to share with you.

Enjoy this Q&A, check out the Reader Meet Writer replay (find that here) and let us know what you think about BOYS OF ALABAMA. And then plan to keep an eye out on what comes next from Genevieve Hudson.

Enjoy this Q&A, check out the Reader Meet Writer replay (find that here) and let us know what you think about BOYS OF ALABAMA. And then plan to keep an eye out on what comes next from Genevieve Hudson.

Q: Some writers love the idea of residencies, while others find the long stretches of wide-open time paralyzing. What has your experience of residencies been like? Can you say a little about pros/cons, and tell us about where you’ve been?

A: I absolutely adore residencies. The handful I have attended (MacDowell Colony, Caldera Arts, Vermont Studio Center, Dickinson House) have been transformative in terms of process and what I can get done. I’m really grateful for the chance to step outside of “normal” life and focus on writing for an extended period of time. In terms of writing, I think time is the most precious resource. I need time to sit with my thoughts, read, let my imagination wander, go on long walks, and play with words. To think. To reread. To scrap pages. All of that is part of the writing process. My process is about unfolding into my work and letting myself feel spaciousness and pleasure. I understand how large swaths of time can feel paralyzing, but in my experience, if I relax into the process and release my expectations, I will find big hunks of unstructured time to be expansive and regenerative and soothing. It is an opportunity to be bored, which is a big gift to creativity. But every writer is different and whatever feels good in terms of writing and process for them is probably the best way forward. I will say, I wrote the first scene for what would later become BOYS OF ALABAMA at Caldera Arts, worked on a major revision of it at Vermont Studio Center and did my final editorial revision at MacDowell Colony. I owe those places so much.

Q: You recently published an essay in Elle magazine about your early boyfriends and how your relationships with them intersected with your own gender identity. In what ways, if any, was the BOYS OF ALABAMA another way of reckoning with the same questions and issues?

A: I see the article in Elle as a companion piece to the book. It’s a way of giving context to my novel-length exploration of boyhood in the American South. I was fascinated with boy culture when I was young, and I immersed myself in it. I skated and played sports and was seen as a “tomboy” and most of my close friends were boys. It took me until puberty to fully understand that me and the boys I surrounded myself with were expected to follow different trajectories. It makes sense to me that my first novel would explore issues of masculinity and how it intersects with Southern culture, queerness, and violence. Through BOYS OF ALABAMA, I wanted to investigate what it meant to be an outsider and a queer youth trying to integrate into boy culture in the Deep South and the toxicity and harm and appeal and comradery that comes with it. I was asking: what does white masculinity do to a culture, a place, a group of people? Those are questions I wrestled with as a young person trying to understand my gender. They are questions I still wrestle with today.

Q: Can you talk a bit about the magic in BOYS OF ALABAMA? Do you see the novel claiming a spot in the tradition of Southern Gothic?

A: In some ways I do see my novel following in the footsteps of the Southern Gothic tradition. Like the books that made up the genre in the past, BOYS OF ALABAMA elevates the absurdist aspects of the Deep South by exploring ways poverty, religion, and racism have worked to pollute and warp communities. The humor is dark and there is a focus on the outcast, the weirdo, and people on the margins. Of course, with its touches of magic realism, there is a centering and exalting of the supernatural. Max’s magical power can be read as a manifestation of his hidden queerness. He has the power to heal within himself (quite literally) but his fear of revealing it, of what people will think, has caused him to hide his power. So instead of showing his true nature, he turns inward and his strength and his gift get warped and end up being the source of harm and pain.

Q: During your Reader Meet Writer virtual event, you gave a great reading list. What is one book that you think deserves more attention?

A: Godshot by Chelsea Bieker is an outstanding novel that came out earlier this year. It focuses on a young girl who is dealing with the loss of her mother and navigating her place in a strange Christian cult in California’s Central Valley that believes they can bring back the rain and free the farmers from a devastating drought. It is all things a novel should be. It’ll break your heart.

Q: What are you working on now, if you don’t mind saying?

A: I am writing a short story for a photography art book that will be published in Europe later this year. The art book explores and documents the gender transition of a Norwegian woman. My story serves as a separate piece that is in conversation with the photo project. I’ve also just started a new book. It’s a road trip novel about friendship, where two buddies reunite in their old college town in the South for a friend’s wedding. Trouble ensues.